History of Lake, Porter, and LaPorte, 1927County history published by the Historians' Association . . . .

Source Citation:

Cannon, Thomas H., H. H. Loring, and Charles J. Robb. 1927.

History of

the Lake and Calumet Region of Indiana, Embracing the Counties of Lake,

Porter and LaPorte: An Historical Account of Its People and Its Progress

from the Earliest Times to the Present.

Volume I. Indianapolis, Indiana: Historians' Association. 840 p.

HISTORY OF THE LAKE AND CALUMET REGION OF INDIANA

CHAPTER VIII.

INDIAN PEACE -- FUR TRADING ACTIVITIES -- THE BAILLY HOMESTEAD -- FORT

DEARBORN REBUILT -- THE FUR TRADE -- AMERICA FUR COMPANY -- TH FIRST WHITE

SETTLER -- THE BAILLY FAMILY LIFE.

58

The second war with England definitely settled British interference with our Indian affairs as they considered it no longer an advantageous policy to pursue and it further definitely fixed American title to the lands south of the Great Lakes as it existed before the war. An attempt was made by the British commissioners to help their Indian allies in the treaty which closed the second war with England; their purpose being an Indian nation in the already established American Northwest territory, but excepting Eastern Ohio where white settlements were definitely and firmly fixed. The American commissioners refused to consider the proposition and stated they would break off negotiations if the British commissioners insisted upon the setting aside of American territory for the Indian tribes. The British commissioners yielded and the Indians were left to their fate to make the best terms they could with the Americans for peace. The Pottawattomies in 1815 made a new peace agreement with the Americans and in a short time the tribes generally were glad to accept the peace terms offered them.

In 1816, Capt. Hezekiah Bradley with two companies of infantry rebuilt Fort Dearborn on the Chicago River which was destroyed during the war. It had been ordered abandoned by Hull as impossible of defense and the seventy men, women and children who occupied it were attacked by Pottawattomies and Winnebagoes on their retreat from the Fort. Some Miamis who were supposed to be friendly to the United States were sent to aid them in their retreat but the Miamis joined the Pottawattomies and Winnebagoes and the result was a massacre, a few survivors surrendering on the promise they would be sent to Detroit. Shaubena and a few other Indians were guarding the prisoners and intended to carry out the agreement but many of the savages insisted on the scalps of the prisoners and as they were in the majority it is doubtful if the prisoners’ lives would have been spared but for the arrival of Shauganash, “Billy Caldwell,” who by threats and persuasion obtained possession of the prisoners and eventually brought them safely to a white settlement.

After 1815 the border enjoyed peace and tranquility. Trappers and traders returned to their favorite haunts and a new era was about to open. John Kinzie, called by many the father of Chicago, reopened his trading

59

store there after the arrival of the troops and Jean B. Beaubien also settled there. A short time later Francis LaFramboise became a resident and as a fur center Chicago now became generally known. The various divisions of the Northwest Territory swarmed with agents of the American Fur Company, organized in 1809 by John Jacob Astor of New York, and the North West Company, the Mackinaw Company, and the South West Company shortly came under Astor’s control, which gave him a monopoly of fur trading in the Great Lakes territory. The practices of the American Fur Company in dealing with Indians were of the most pernicious character and though the Government sought to protect them by proper laws, these were not generally observed.

All the evidence existing show that improper influences and even bribery of government agents was resorted to, in order to thwart the Government in its efforts to obtain justice for the Indians in their relations with the Fur Company, who traded them inferior merchandise for furs. Among the methods resorted to by the American Fur Company, in competition with independent traders was to offer more merchandise for furs than the independent traders could allow and as a result the independent traders were forced to discontinue business, or as generally happened, were taken into the employ of the Fur Company. With competition removed, the Fur Company resorted to its regular tactics of giving the Indians a small amount of inferior merchandise in exchange for furs and, if these were not forthcoming in sufficient quantity, whiskey was used as an incentive, and finally whiskey became the principal article of merchandise offered.

The reaction was pronounced, and drunkenness, laziness and shiftlessness, developed to such an extent that the Indian ceased to be interested in obtaining furs, and the Fur Company, through their own greed, destroyed their principal source of supply and lowered the moral standard of the Indian so that he became a useless loafer in and around the settlements. The best known of all the traders was Joseph Bailly of Bailly Town, located on the north bank of the Little Calumet and about two miles west of Valparaiso, or as it was then called, Porter. It is claimed that as early as 1796 Bailly Town under the name of Little Fort was used by fur traders as a storage point and before the arrival of Joseph Bailly, it was a headquarters for Alexander Robinson in his fur trading activities.

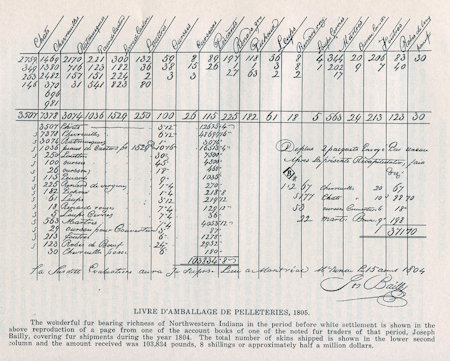

Bailly Town became widely known and was a great resort for travelers who were always assured of a warm welcome by its cultured owner and his family. In Hon. John O. Bower’s narrative of the “Old Bailly Homestead,” which follows, the reader will note many interesting occurrences associated with life on the frontier during the Bailly period, and the volume of business done by Mr. Bailly in furs proves the remarkable richness of the fur bearing territory in which he dwelt. Mr. Bowers is a prominent

60

attorney and historian of Gary, Indiana, and a recognized authority on the history of the early settlement period in the Lake and Calumet region of Indiana.

THE OLD BAILLY HOMESTEAD.

This is a story of the first white family that settled in Northwestern Indiana, together with an account of that settlement. This year, 1922, marks the one hundredth anniversary of the settlement. It requires some effort of the imagination to establish in our minds a picture of this country at that time, but the story about to be related can best be appreciated by a little reflection upon the primitive conditions that then existed and the environment of such settlers. Although Indiana had become a state, yet her capital was still away down at Corydon, near the Ohio River, and nobody knew where the permanent capital of the state would be. The only organized counties in the state were in the southern and southeastern part of the state. The territory comprising what is now Marion County was a wilderness, and the entire northern Half of the state was still inhabited by Indians.

Around the south end of Lake Michigan, the Pottawattomies owned and were in possession of the land. The country was composed mainly of almost impenetrable marshes. It was inhabited by wild animals and wild men. There were no roads but Indian trails. There were no settlements between Fort Dearborn and Fort Wayne. Fort Dearborn contained a few soldiers and their families, in the swamps near the mouth of the Chicago River. There was a trading post over on the St. Joseph River, near the present site of Bertrand, then called Parc aux Vaches, and Isaac McCoy and his wife were about to open a Baptist mission school, known as Carey mission, among the Indians, at a place near the present site of Niles. Michigan was a territory inhabited largely by Indian tribes.

THE FIRST WHITE SETTLER.

So, what was there here on the marshes of the Calumet to attract or induce settlers to come hither? And who was the first settler and why came he hither? Certainly he was not a farmer, seeking land for tillage; and surely he came not in a schooner drawn by oxen or horses, for these marshes gave no promise to prospective tillers of the soil, nor offered any inducements to those seeking sunny climes or mudless roads. What were the inducements? What sought he here, and what experience, if any, did he have to fit him for residence and occupation among the Indians and on the boundless marshes to the west and south, and limitless forests to the east and north, in this land of the Pottawattomies, who recognized no geometric lines nor allotted any parcels of ground? No, this adventurer

61

cared not for surveyor’s lines, nor townships nor sections, but he knew what he wanted, and he was getting what he sought.

The name of this man, the head of the first family, was Joseph Bailly. He was the son of Michael Bailly de Messin, an aristocratic Frenchman of Quebec, in which city Joseph was born in the year 1774, the city at which occurred the decisive battle by which France lost an empire in the new world, and by which the social complexion and the political history of this country were so changed that only conjecture can answer the question, “What if France had won and had sat at the peace table in 1763 as the victor, and not the vanquished?” The father having died when Joseph reached young manhood, leaving the family, consisting of the widow, two sons, Joseph and William, and a daughter, in want, it became necessary for him to select an occupation and assume the role of provider for the family. Having had a fair education, being a good penman and being also of an adventurous spirit, he left his home town and went out West and engaged in the biggest line of business of his day, the fur trade, at the center of its activities, Michillimackinac (later called Mackinac).

THE FUR TRADE.

The story of the fur trade at this trading post is a long and thrilling one, but it would be foreign to the subject of this sketch except in so far as the activities at the place were incident to and became a part of the experience of the main character in this story. And so in passing, it may be well to note that the fur trade, which had been going on for more than a century, extending back even to the days of Cartier and Champlain for its beginning now was assuming great proportions. The French and the English, and particularly the French, had realized the demand for furs in the Old World. Here around the lakes were animals which yielded the finest furs in the world. Here were the beaver, the silver fox, the red fox, the wolverine, the mink, the otter, the lynx, the black bear, the wolf, and many other fur bearing animals in vast numbers. Their skins found ready sale in the centers of wealth and fashion in Europe.

The trade occupied the attention of companies and men of means and influence. The Indians in the early days of the trade, took their pelts to Quebec and Montreal, but as the demand increased, and the opportunities for profits augmented, adventurous spirits went out through the forests, paddling their canoes across lakes and along rivers, learning the language of the Indians and adopting their mode of life. They married squaws and reared families. In starting upon their expeditions, they loaded their boats with axes, kettles, knives, fire-arms, ammunition and various trinkets, and sometimes with rum, and proceeded to remote nooks and crannies of the wilderness to exchange the same for peltries com-

62

posed of the skins of the above mentioned animals. The men who rowed the boats and performed the labor were called voyageurs or engages. The bush-rangers, or rovers of the forest, were called coureurs des bois.

TRADING POST ESTABLISHED.

As the trading developed and fell into the hands of men and companies with large amounts of capital, trading posts were established at advantageous places, with their superintendents, their complements of voyageurs, canoes or bateaux and pack-horses. These posts were the central points for the merchandise to be used in bartering, and the assembling of the peltries. In the spring time, at the close of the hunting and trapping season, from the widely scattered posts throughout the Indian hunting grounds by boats and by pack-horses, came the peltries which were sold or delivered to the several companies, the chief of which, after the year 1809, was the American Fur Company, the principal stockholder of which was John Jacob Astor, who, as a poor emigrant boy, began his business career in New York without capital save his energy, thrift and talent, and through efforts and various manipulations, sometimes unduly selfish, in the fur trade, amassed the greatest fortune of his day in America, some $30,000,000. And at one time during the first quarter of the last century, when the trade was at its peak, fully nine-tenths of the fur traders of the Northwest were engaged by or were under the influence of that company. The policy of the company was monopolistic. When an independent trader started a trading post, Astor started one in the same locality, with instructions to his agent to offer inducements which would get the pelts.

Mackinac normally was a village of about 500 inhabitants, mostly Canadian-French and French-Indian, whose chief occupation in the summer time was fishing and in the winter time hunting. There were not more than twelve white women on the island. The remainder of the female population was Indian or French-Indian. During the summer time here congregated the employees of the fur company, bringing their peltries from the various trading posts throughout a scope of territory bounded by the British dominions on the north, the Missouri River on the west and the white settlements on the south, which employees aggregated about 2,500 men. Hither came also Indians in like numbers from the shores of the upper lakes, who made this island a place of resort. The tents of the traders and the wigwams of the Indians covered the beaches.

The voyageurs all were Canadian-French. They were of a happy-go-lucky type and were the only persons or class fitted to endure the hardships incident to their occupation, for it should be remembered that the voyageurs were not provided with shelter and their luggage was restricted

63

to twenty pounds carried in a bag. Their daily ration per man was a pint of “lyed corn” (hominy) and four ounces of tallow, with flour on Sunday for pancakes. Each batteau had a crew consisting of a clerk and five men, the voyageurs — one man to steer and four to propel the craft.

In the latter part of the summer the peltries were sorted, counted, appraised and packed in the company’s large warehouses, to be ready for shipment to Mr. Astor in New York. Millions of dollars worth of merchandise was exchanged annually with the Indians. The foregoing will serve to indicate the character and the magnitude of the business in which Mr. Bailly had embarked and the sort of environment attending the so-called Indian fur trader of that day.

STARTED AUGUST 17, 1796.

The writer of this article does not know just when nor where Mr. Bailly established his first trading post; but it has been thought by some persons familiar with the history of his early business activities that he may have had his post on the Grand River as early as 1793, or thereabouts. His books of account, kept in orderly fashion, with dates duly inserted, which are still accessible, indicate, however, that they were opened and kept for some time at Michillimackinac, for it appears from these books that here at Michillimackinac, on the 17th day of August, 1796, he opened these books of account which were kept by him in his own handwriting in the French language. His business for that year was very small, but it grew from year to year. Values were designated in pounds and shillings. The books indicate that the period from 1802 to 1805 was the most prosperous.

His grand livre (ledger) shows that “pelletries” (peltries) were debited during the months of June, July and August, 1803, to the amount of 99,723 pounds, thus aggregating nearly a half million dollars. By that time he had established trading posts or places of business at several points in Michigan Territory, as on the Grand River, the St. Joseph, at Parc aux Vaches (near Bertrand), and other places. Transactions at such places were designated in his index as “A Venture a la Grand Riviera,” “A Venture a la St. Joseph,” ‘‘A Venture a la Kikalimazo,” “A Venture a la Wabash,” etc. Then there are entries under such headings as “Monsieur J. B. Baubien,” etc. (See next page.)

So, fluctuating some from time to time, the business was carried on for many years. The period covered by the War of 1812 was below the average in volume of business, at which time, from the entries in his books and the copies of his letters, it appeared that his business extended from Mackinac in the north around the Grand, the St. Joseph, the Kinkiki (Kankakee), the Iroquois and the Wabash rivers. It has been said by local histo-

64

65

rians that he was for some years employed by the American Fur Cormpany, especially while, it is said, he was associated with Alexander Robinson (later Chief Che-Chebingwa), while they were at Parc aux Vaches (now Bertrand), on the St. Joseph River; but the books which purport to be “Livre pour les affaires du Parre a Vaches Lo. 2 Aoust 1804,” do not so indicate. Robinson's name does not appear.

However, it may be proper to note that many of the great traders were in the employ of the American Fur Company, among them being John Kinzie and Guerdon S. Hubbard of Chicago. Mr. Kinzie at one time was at Bertrand in the employ of Mr. Astor. It is possible, or even probable, that Mr. Bailly may have been in some manner associated with Mr. Astor. It is quite certain he sold or delivered his furs at Mackinac, and it may be that he bought or obtained merchandise from Astor or the company, but the books do not indicate such transactions.

WEDS FRENCH-INDIAN.

It is to be noted that Mr. Bailly made two adventures not recorded in his books of account — they were of matrimonial character. The first of these was his marriage with a daughter of an Indian chief. It is said that this marriage was consummated in true Indian fashion; Mr. Bailly paid for his bride to her father in horses and other things of value specified by the chief. The couple became the parents of six children — five sons, Alexis, Joseph, Mitchell, Philip and Francis, and one daughter, Sophie — of whom Sophie was the youngest.

It is said that during these early years of his career, Mr. Bailly resided with his family at his post on the Grand River, near an Indian village, a few miles east of the present town now called Ionia, and that the above-mentioned children were born there. It is related that Mr. Bailly sent his sons to school at Montreal, Canada, and that when they were old enough to attend he put them all in a canoe to go down the Grand River and then on Lake Michigan to Mackinac, and thence to Montreal, but that before they had gone far Francis, the youngest, jumped out of the boat and swam ashore, saying that he did not want to be educated, but wanted to go back to the tribe and become a “medicine man”; and he returned and remained with the tribe until it was removed to a reservation, at which time he went to and settled in Oceana County on a farm.

Alexis, the oldest, having finished his work in school, returned to his father at Mackinac in 1811, and thereupon became a clerk in the service of the American Fur Company at Prairie du Chien, on the Mississippi River. Later he was stationed for the company at Mendota, Minnesota, and while here he married Lucy Faribault, a daughter of Jean Baptiste Faribault, a noted trader. About 1840 he moved to Wabasha and estab-

66

lished a trading post. He became a member of the first territorial legislature of Minnesota. He died in 1861. Of the other sons, brothers of Alexis, Joseph became a printer; Mitchell a sculptor, and Philip an engraver.

Sophie, the daughter, became a teacher, having taught for several years at St. Ignace. She married Henry Graveraet. The husband and their only son, Garrett, recruited and were officers in Company K, First Michigan Sharpshooters, and both were killed in the campaign before Richmond, near the close of the Civil war. A grandson of Sophie, John C. Wright, son of Rosine Graveraet Wright, has written several books, some pertaining to Indian legends which he learned from his grandmother. It would be beyond the province of this paper to follow the descendants of the above-mentioned children of Mr. Joseph Bailly, but in passing it may be said that many of them held responsible positions in business and official life.

At this point it becomes necessary to relate that some disagreement or estrangement occurred between Mr. Bailly and his Indian wife, and a separation took place, Mr. Bailly having made provision for the education of his children.

Later, probably about 1810, he entered upon a second marital adventure by taking unto himself, according to the common-law marriage customs of the time and place, a widow of French-Indian blood, whose maiden name was Marie LeFevre. She had been married to one De La Vigne, but she had taken her two children, Agatha and Therese, from their home on the Riviere des Raisins, and gone to her people at the village of L’Arbre Croche, near Little Traverse Bay. In company with members of her family, she went to Mackinac to trade.

Through the suggestion of a friend, Mr. Bailly sought acquaintance with her. Each admired the other. He promised to be a father to her two girls and she promised to be a mother to the children of Mr. Bailly. They agreed to live together as husband and wife, and he thereupon introduced her to his clerks and servants as Madame Bailly, and, so far as we know, they lived together happily ever afterwards. It will be borne in mind that in that far day, in that remote settlement of the wilderness where priests, preachers and civil officers were few, the common law type of marriage was usual, few marriages having been solemnized by church or state. It is stated that this marriage was duly solemnized in some later year.

Just how long Monsieur and Madame Bailly continued to reside at Mackinac does not appear, but it does appear that some years later they resided on the St. Joseph River, most likely at Parc aux Vaches. It is recorded that at one time Mr. and Mrs. Bailly made a trip on horseback

67

from the Straits of Mackinac to Southern Michigan. It is likely that as the fur-bearing animals grew scarce in that locality or around established posts, it became advisable to establish new posts on the wilder frontiers. So, in 1822, Mr. Bailly, with his family and household goods, came and located here in the heart of the Pottawattomie country, on the north bank of the Little Calumet River, at a point a short distance northwest of what is now the town of Porter in Porter County, about half a mile north of the old Indian territorial boundary line, now usually called Indian Boundary Line. He thought he was locating in Michigan Territory, in which he had lived for so many years.

At first it may seem strange that the boundary line of a state six years old was undefined and unknown, but when you recall that that old territorial line had been merely designated, without a survey, by the old ordinance of 1787, for the division of the Northwest Territory, as a line due east and west, through the most southerly point of Lake Michigan, and that the new line which had been designated in the Enabling Act for the admission of Indiana Territory as a state was to be a line ten miles north of the old line, and had not been surveyed until the year 1827, it is not surprising that he should have been ignorant of or uncertain about the exact location. The Fulton survey of the old line had probably been made but may not have been well defined. It is related that at so late a date as 1829, a Mr. Crawford, a resident of Elkhart, Indiana, was appointed sheriff of Cass County, Michigan Territory, and accepted the office and discharged the duties thereof, in the belief that he was a resident of Michigan Territory. (It would require volumes to contain a complete history of this old line and its consequences, for it kept national politicians busy during several administrations and culminated in the so-called ‘‘Toledo war,” in which bayonets glistened, but in which no blood stained the soil.) It will be remembered that at this time Fort Dearborn was simply a military post with a few soldiers and a few white families in civil life; that there were no settlements between Fort Dearborn and Fort Wayne and that the nearest trading post was on the St. Joseph River.

When Mr. Bailly arrived, he carried in his pocket a paper, of which the following is a copy:

“Detroit, 15 March, 1814.

“To All Officers Acting Under the United States:

“The bearer of this paper, Mr. Joseph Bailly (Ba-ye), a resident on the border of Lake Michigan, near St. Josephs, has my permission to pass from this post to his residence aforesaid. Since Mr. Bailly has been in Detroit, his deportment has been altogether correct, and such as to acquire my confidence; all officers civil and military, acting under the authority of the American government will therefore respect this passport which I

68

accord to Mr. Bailly, and permit him, not only to pass undisturbed, but if necessary yield to him their protection.

“H. BUTLER.”

“Commandt. M. Territory and its Dependencies, and the Western District of U. Canada. To all Officers of the A. Government.”

SESSIONS OF WAR.

It will be noticed that in 1814 he resided upon the St. Joseph River. The War of 1812 was still in progress and the fur trade was suffering from the invasion on the frontier by the British. In the fall of 1814 Mr. Bailly was arrested by the United States troops on suspicion that he was a spy in behalf of the British. He remained in prison several months, and was then released without trial. It has been said also that at one time he was seized by the British.

A letter written by Mr. Bailly, dated 1805, at Parc aux Vaches, was addressed to Mr. Louis Bourre of Fort Wayne, relative to procuring licenses which were required of all those who traded with the Indians. This shows that he obtained licenses for agents at Parc aux Vaches the St. Joseph, the Kankakee and the Iroquois rivers, for he speaks of these agents as “my employes.”

It therefore is likely that just prior to his locating upon the Calumet, he had been residing at Parc aux Vaches. At the time of his arrival, his family was composed of his wife, Marie, and four children, Esther, Rose, Ellen or Eleanor, and Robert.

The first house erected at the new settlement was a log cabin, which he built on the north bank of the Little Calumet. It was doubtless summer time, for apparently he underestimated the volume of the water of this stream in flood times, for when the high waters came, they entered the cabin and covered the floor. The servants next day tore down the little house and carried the logs up to the top of a high knoll, the present site of the buildings, the same being a commanding spot, overlooking the river and the valley below, and there they re-erected the cabin. Here, from time to time, several other buildings were erected; houses of the fur trade and houses for servants were built. A better dwelling was erected in 1834.

ONLY WHITE SETTLER.

Here, then, on the banks of the Calumet (in those days called Calumic or Colomique) Mr. Bailly carried on his fur trade with the Indians. For ten or twelve years he was the only white settler in this region. Here the Bailly children passed their childhood, playing with the children of the copper colored natives, and learning to read and write. Hither came

69

priests who conducted religious services and sought to convert the Indians to the Christian religion. During this period of his residence in the Calument region, he obtained his mail at Fort Dearborn. The route to Fort Dearborn lay northwesterly from the post and across to and through the sand hills (now called Dunes) to Lake Michigan, at a point north of the place now known as Baileytown; thence westerly along the beach.

Mr. Bailly’s peltries were carried on pack-horses across to Lake Michigan at the point above mentioned, and there put into row boats, about thirty feet in length, and rowed by man power to Mackinac. He had in his employ Canadian-Frenchmen and the Indians. He kept a store, stocked with such goods and trinkets as the Indians desired, which wares were bartered for peltries. Some time during the late ‘20s the values of articles were designated upon his books in dollars and cents, instead of pounds and shillings. It should be noted also that about this time Mr. Bailly became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

The two older daughters, Esther and Rose, born respectively in 1811 and 1813, had been sent to the Carey Mission school at Fort Wayne, a Baptist institution, before the family located on the Calumet, — this, notwithstanding the fact that the Baillys were devout Catholics. Here attended also the children of the Beaubiens of Fort Dearborn.

I quote the following from “The Story of a French Homestead in the Old Northwest,” by Miss Frances Howe, a granddaughter of Mr. Bailly:

“In the homestead, the evenings were devoted to some form of instruction. The family spent their evening hours as all well bred families of that period did. The ladies were employed in needle work, while grandfather read aloud or taught the children. The servants, French or Indian, gathered around the huge fireplace in their own separate quarters, sung their ditties and told tales. Sometimes they were called into the family sitting room to listen to simple lectures on geography or to receive instruction regarding the approaching feast or fast.

“Grandfather must have been very well satisfied with the education given at Carey Mission, for after building his home, he continued to send his children there year after year, until they were old enough to be taken to Detroit.”

EDUCATIONAL ADVANTAGES.

Mr. Bailly gave his children about all the educational advantages that were available at that time. His family associated with the first families of Chicago. It is said the girls were intelligent, cultured and refined. As much of the traveling of the early days was done in the saddle, the Bailly girls acquired the art of horseback riding. They traveled to and from Fort Dearborn along the beach in this manner. The family being quite religious, much attention was given to religious instruction. The

70

71

sharp contrast between the educational facilities of the present, the comfortable and even luxurious environment of student life of this day, and the meager opportunities and difficulties incident to the acquisition of even a fair education in that day, may be seen in the following description taken from “Old Homestead” (1907) by Frances Howe, concerning her Aunt Esther and her mother when taken to Detroit for their first com-munion and education in 1826:

“Early in December the wardrobes of the two girls were in readiness to be packed in such shape as to make a proper bundle for a pack-saddle. There were likewise tents, cooking utensils and provisions for a whole week; so all together there was packed enough to make two sturdy ponies. Two saddle horses also were made ready for grandfather and one hired man, an Indian. Farewells were not brief, for the girls would be absent from home for a whole year, with little opportunity for exchange of letters. Each little girl was strapped securely on the top of a load, and so they set forth on the journey to Detroit.

“At that day in the long stretch of territory between Detroit and Chicago (still only Fort Dearborn), there were only two points where travelers could rest under the shelter of a roof — White Pigeon and the Bailly trading post. There were no roads excepting the Indian trails, hidden at that season by the snow. . . . The pack horses set the pace, so the journey was slow. It took a whole week to cover 250 miles . . . The horses of that period were accustomed to feed upon the upland prairie grass, so all the stabling they required was the lee side of a bit of timber, the dried grass from which the guide swept away the snow drift served for both bedding and fodder. A fallen tree would serve as a back log for the camp fire, around which the two tents were pitched. The evening meal, cooked on the camp fire, being disposed of, the two girls, wrapped in blankets, slept on a couch of furs in their own tent. In the morning, up by dawn to an excellent breakfast, then strapped to the pack-horse for a whole day, lunch in the saddle, glad enough they were when evening came to restore circulation through benumbed limbs by helping to sweep away the snow from the site of their camp. Such were the efforts which it was necessary to make in order to obtain a proper education in the Middle West a century ago.”

SON DIES OF TYPHOID.

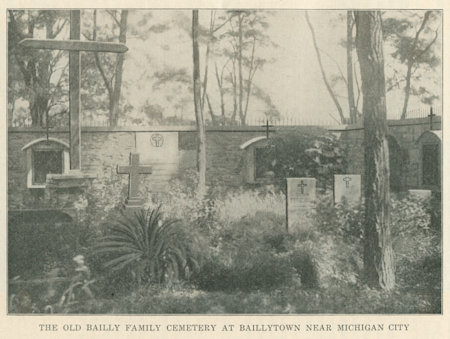

In 1827, while attending the Carey Mission school, near the present site of Niles, Robert Bailly, the son, then ten years old, became sick with typhoid fever and died. His grave was the first in the family cemetery, located half a mile north of the old homestead. Mr. Bailly afterwards, in the same year, erected a chapel as a memorial to his son, whose death was a great blow. Some years later, Hortense, the youngest daughter, was

72

sent to school at Washington, D. C. As before stated, priests at times came here and religious services were held. Before the building of the chapel, services were held in the residence, the parlor being used for the sacristy where confessions were held, and the dining room as the place where mass was celebrated. For a time this mission was the only Catholic mission between Detroit and Chicago.

Here Indians, in their migrations, spring and fall, pitched their tepees and tarried, for they were always welcome at Bailly’s. Here paused the white travelers in their journeys between Fort Dearborn and Detroit. In the late ‘20s and the early ‘30s the place was popular and received many compliments from travelers in their descriptions of their journeys through the wilderness. Here was civilization in a land of savages. Here were books, literature, education and refinement. Here Mr. and Mrs. Isaac McCoy stopped on their long journey when they followed the Pottawattomies to their new and distant home in the Far West. Interesting, even thrilling, the history of those primitive days, but the only constant thing in this world — change — had marked this frontier for its own.

OLD TRAIL UNSUITABLE.

The old Indian trail leading by the old Bailly trading post, over which the Indian tribes had traveled and brought their furs, did not suit the adventurous and property-acquiring white man; so in 1831 a mail route was established between Detroit and Chicago. This route in the main followed the old trail of the red man. At first the mail was carried in knapsacks, on the backs of two soldiers on horseback; but still the white man was impatient for better roads for transportation. The road was improved further so that traveling might be made by wheeled vehicles, and in 1833. came the mail carrier with his buckboard, innocent of springs, and in the same year the time honored stage coach began to wend its way across the wilderness of Southern Michigan and Northern Indiana, passing through what is now Porter County, by the Bailly homestead. Trips were tri-weekly. With the stage coach came the second, third, fourth and other white settlers, to the region in which Mr. Bailly had located. These newcomers were not fur-traders; they were not competitors of Bailly, for by this time the title to the land had passed by treaty or purchase from the Pottawattomie nation to the United States, and surveyors of the latter already were dividing the erstwhile domain of the red man into little squares called townships and sections, marked by little posts and described by little plats. The decline of the fur trade was casting its shadows before. The handwriting that spoke the passing of the happy hunting grounds and the trader’s profits was on the wall.

A description of the Bailly trading post and the experiences of travelers in the early days of the stage coach appears in “A Winter in the

73

West,” in the form of letters and diary entries of the author, Mr. Huffman, then an editor of certain New York periodicals. I quote from an entry dated January 1, 1834, which covers the journey then recently made from Door Prairie, LaPorte County, to the Lake Michigan beach, as follows:

“At last, after passing several untenanted sugar camps of the Indians, we reached a cabin prettily situated on the banks of a lively brook wending through the forest. A little Frenchman waited at the door to receive our horses, while a couple of half-intoxicated Indians followed us into the house, in the hope of getting a ‘nestos’ (a ‘treat’) from newcomers. The usual settlers’ dinner of fried bacon, venison cutlets, hot cakes and wild honey, with some tolerable tea and Indian sugar — as that made from the maple tree is called in the West — was soon placed before us; while our new driver, the frizzy little Frenchman already mentioned, harnessed a fresh team and hurried us into the wagon as soon as possible. The poor little fellow had thirty miles to drive before dark, on the most difficult part of the route of the line between Detroit and Chicago. It was easy to see that he knew nothing of driving the moment he took the reins in hand; but when one of my fellow travelers mentioned that the little Victor had been preferred to his present situation of trust from the indefatigable manner in which, before the stage route was established last season, he had for years carried the mail through this lonely country — swimming rivers and sleeping in the woods at all seasons — it was impossible to dash the mixture of boyish glee and official pomposity with which he entered upon his duties by suggesting any improvement as to the mode of performing them. Away then we went, helter skelter, through the woods, scrambled through a brook and galloped over an arm of the prairie, struck again into the forest. A fine stream, called the Calamic, made our progress here more gentle for a moment. But immediately on the other side of the river was an Indian trading post, and our little French phaeton, who, to tell the truth, had been repressing his fire for the last half hour, while winding among the decayed trees and broken branches of the forest—could contain no longer. He shook the reins on his wheel-horses and cracked up his leaders with an air that would have distinguished him on the Third Avenue and been envied at Cato’s. He rises in his seat as he passes the trading house; he sweeps by like a whirlwind; but a female peeps from the portal, and it is all over with poor Victor.

Ah, wherefore did he turn to look?

That pause, that fatal gaze he took

Hath doomed * * * his discomfiture.

“The infuriated car strikes a stump, and the unlucky youth shot off at a tangent as if he were discharged from a mortar. The whole operation was completed with such velocity that the first intimation I had of what

74

was going forward, was on finding myself two or three yards from the shattered wagon, with a tall Indian in wolf-skin cap standing over me. My two fellow passengers were dislodged from their seats with the same want of ceremony; but though the dejecta membra of our company were thus prodigally scattered about, none of us, providentially, received injury. Poor Victor was terribly crestfallen; and had he not unpacked his soul by calling upon all the saints in the calendar in a manner more familiar than respectful, I verily believe his tight little person would have exploded like a torpedo. A very respectable looking female, the wife, probably, of the French gentleman who owned the post, came out and civilly furnished us with basins and towels to clean our hands and faces, which were sorely bespattered with mud; while the gray old Indian before mentioned assisted in collecting our scattered baggage.

START AGAIN ON HORSEBACK.

“The spot where our disaster occurred was a sequestered, wild-looking place. The trading establishment consisted of six or eight log cabins of a most primitive construction, all of them gray with age so grouped on the bank of the river as to present an appearance quite picturesque. There was not much time to be spent in observing its beauties. The sun was low, and we had twenty-five miles yet to travel that night before reaching the only shanty on the lake shore. My companions were compelled to mount two of the stage horses, while I once more put the saddle on mine, and leaving our trunks to follow a week hence, we swung our saddle-bags across the cruppers and pushed directly ahead. A few miles of riding through the woods brought us to a dangerous morass, where we were compelled to dismount and drive our horses across, one of our party going in advance to catch them on the other side. A mile or two of pine barrens now lay between us and the shore, and winding rapidly among the short hills covered with this stunted growth, we came suddenly upon a mound of white sand at least fifty feet high. Another of these desolate-looking eminences, still higher, lay beyond; we topped it; and there, far away before us lay the broad bosom of Lake Michigan.

“The deep sand, into which our horses sank to the fet-locks, was at first most wearisome to the poor brutes, and having yet twenty miles entirely on the lake shore, we were compelled, in spite of the danger of quick sands, to move as near the water as possible. But though the day had been mild, the night rapidly became so cold that before we had proceeded thus for many miles, the beach twenty yards from the surf was nearly as hard as stone, and the finest macadamized road in the world could not compare with the one over which we now galloped. Nor did we want lamps to guide us on our way. Above, the stars stood out like points of light; while the resplendent fire of the aurora borealis, shooting

75

among the heavens on our right, were mocked by the livid glare of the marshes burning behind the sand hills on our left.”

The author of that sketch does not give the name of the owner of the trading post, but it could have been none other than Bailly for his was the only post in that locality, and the only one whose buildings could have been “gray with age.” Bailly had been there about twelve years. Perhaps the embarrassing circumstances above narrated may serve to excuse Mr. Hoffman for this omission to give the name of the post and of the good angel who administered to his needs. At the coming of the farmers, artisans, mechanics and teachers, it is apparent that the exit of the trader was at hand. With the closing of his business passed the coureurs des bois, the voyageurs, and finally the aboriginal occupants of the land, the red men of the forest. Quoting from another on a like situation, but applicable here:

“The ancient Indian highway * * * which for nearly a century had been worn deep by the feet of traders, soldiers and priests, and had resounded with the songs of the coureurs des bois, voyageurs, and engages, all speaking the soft language of France, knew them no more.”

IMPROVEMENTS STARTED.

With the early ‘30s came all sorts of proposed developments — highways, state and national, railroads, canals, the location of town sites, on paper, and wild speculation in western lands. Mr. Bailly tried to adapt himself to the new day. He purchased many sections of land. He became interested in the location of a harbor at the southern end of Lake Michigan. He foresaw that eventually somewhere at the southerly end of this great inland sea a great commercial center would develop, but which at that time had not appeared. By the treaties of 1832 at Tippecanoe, and 1833, at Chicago, allotments were made to members of the Bailly family. Mr. Bailly caught the spirit of the times and laid out a town site on the north bank of the Calumet, then called the Calumick River, a short distance west of the site of his home and trading post.

He prepared a plat, bearing date December 14, 1833, entitled “Town of Bailly, Joseph Bailly, Proprietor.” He laid it out “four square,” with blocks, streets and alleys. He honored his family in the naming of the streets. One he called Lefevre, after the name of his French-Indian wife. Others were named, respectively, Esther, Rose, Ellen and Hortensia, the names of his daughters. One he named Jackson, doubtless in honor of the President of the United States, and one Napoleon, for the hero of France. The streets running at right angles to the foregoing bore the names of the Great Lakes — Michigan, Superior, Huron, Erie and St. Clair. He had a form of warranty deed prepared and printed especially for use in the sale of lots in this subdivision, leaving only blank spaces for the

76

insertion of the description of the lots being sold, and for the names of the grantees. It appears from his papers that one Daniel G. Gurnsey was acting as his agent in the promotion of the enterprise and the sale of lots.

DIED IN DECEMBER, 1835.

But bright prospects only were to be his. After a few lots had been sold, the health of the trader who had penetrated the primeval forests in his quest for furs had began to fail. He loosened his grasp from his adventures and prepared his estate for administration by other hands. He saw the end approaching and gave directions for his burial in that little cemetery where, years before, he had buried his son. He died in December, 1835, and was buried in accordance with his request. A neighbor by the name of Beck acted as minister and undertaker, as directed by the deceased.

Their daughter, Esther, had married John H. Whistler, a son of Capt. John Whistler, who built the first Fort Dearborn, and was living in Chicago at the time of her father’s death. Rose and Ellen also were in Chicago. Hortense, scarcely twelve years old, still was playing with her Indian playmates at the homestead.

For a time after the death of Mr. Bailly, Mrs. Bailly lived with her daughter, Agatha, who in 1819 had married a prosperous young trader by the name of Edward Biddle, but later returned to the old homestead. Mr. Biddle was a member of a prominent family by that name in Philadelphia. It has been said that at the time of their marriage, “He did not know her language, neither did she understand his, — but love needed no tongue.” Shortly after their marriage they moved into the house which they occupied for fifty years, and in which both died, and which is now the oldest house in Mackinac. They sometimes came in their sloop to visit the Baillys at the old homestead. Mrs. Bailly survived Mr. Bailly until 1866, a devout Catholic, cherishing the memory of her departed husband, Joseph Bailly.

In the year 1841, Rose married Francis Howe, a well-to-do business man of Chicago. He died in 1850, leaving surviving him his widow and two daughters, Rose and Frances. Mrs. Howe and her daughters then returned to the homestead, and thither came also her mother from Mackinac, and once again the old homestead was supervised by the family, and children reared thereon. Eleanor, now deceased, became Mother Superior at St. Mary’s, Terre Haute. And so again the education of daughters at the old homestead began all over, but under very different circumstances from those of the first generation. Rose Howe, the older of the two, was sent to St. Mary’s Institute, at Terre Haute, and was graduated therefrom with honors in 1860. Frances, her sister, also attended the same school.

77

Mrs. Esther Bailly Whistler died soon after the death of her father, leaving surviving her husband and five infant children, Mary, William, John, Joseph and Leo. Her husband soon thereafter moved with the children to Kansas, and died at Burlington, that state, October 23, 1873, aged sixty-six years. He was born in the original Fort Dearborn in 1807. Hortense Bailly married Joel H. Wicker, the first merchant of Deep River. She died many years ago, leaving surviving her husband and a daughter named Jennie, who resides in Michigan. Mrs. Rose Howe and her daughters, Rose and Frances, neither of whom married, are deceased, Frances having survived by many years her mother and sister. Both Rose and Frances were authors of religious books, and Frances wrote “The Story of a French Homestead in the Old Northwest,” as above mentioned. She continued to reside at the homestead parts of each year until the time of her death in 1918 at Los Angeles, California.

ASSOCIATED WITH BEST FAMILIES.

The Baillys associated with the first families of Chicago — the Baubiens, the Kinzies, the Ogdens, the Hubbards and others. They often visited their old acquaintances in that place. There are yet some persons living who remember Mrs. Bailly. She has been described as an attractive woman, quiet and reserved. Of her it has been written: “She was a good woman, and possessed the gift so much prized among her people — that of a good story teller. Her stories quite surpassed the Arabian Nights in interest; and one could have listened to her all day and never tire. They were told in the Ottowan language.” The daughters became women of educational attainments, grace and character.

Mr. Bailey was a brave, adventurous, red-blooded man, who loved the wild, the primitive, the natural. Endowed with paternal instincts, he reared a family in culture and refinement according to the best standards of his time and place. His books of account were neatly kept. Copies of his letters indicate civility, politeness and business capacity. Relative to the manner and characteristics of Mr. Bailly, it is stated in “Reminiscences of Mackinac Island” that he was somewhat loud in speech and laughter, but good-natured, and hospitable: “One was never at a loss to locate him, no matter what part of the island might contain him. His loud laughter and speech always betrayed his whereabouts. He was an exceptionally good-natured man, fond of entertaining his friends.” The proposed “Town of Bailly” was not built, but a “Baileytown” near the site of the proposed town remains on the map, as the name of a settlement, which serves to perpetuate the name of the first settler in this region.

The Bailly library had been preserved by Miss Frances Howe at the old homestead. It consisted of some 200 or 300 books, some in English, some in French, many of which were bound in leather, some historical,

78

some religious, some biographical, some classic fiction and some school books, all showing a taste for good literature. Here was “Plutarch’s Lives” in eight volumes (Ed. of 1911), “Paradise Lost” (1831), “Scottish Chiefs” (1836), “Robinson Crusoe” (1847), “Waverly Novels” (1839), Dickens Works, Works of Montesquieu (Oeuvres de Monsieur De Montesquieu de L’Esprit Des Loix 1769), “Historic Gil Blass” (1829), Shakespeare’s Works, “Last Days of Pompeii,” and many others. Here were the school books used by the Bailly girls when at school; English Grammar, by Lindlay Murray (1822), English Reader and English Exercises, by the same author, English Grammar, by Samuel Kirkham (1824), Algebra by Le Croix (1825). Here also was a copy of Hoyle’s Games Improved (1829), for even in that far day, they went “according to Hoyle.” Here also were religious books in the Ottowan language for the education of the Indians.

The books of account kept by Mr. Bailly, some forty in number, cover the period from 1796 to the time of his death. Among the scores of names of men with whom he dealt upon the books were: John Kinzie, William Burnett, Robert Forsythe, Tousaint Pothier, Charles Chandonnet, Honore Bailly, John Dousman, Edward Biddle, Louis Bourre, Francois Bailly, Jacques La Salle, Joseph Bertrand, Joseph Nuemannville, Oliver Newberry, Lafromboise & Schindler, Jean Baptiste Barreau, Samuel Solomon, La Succession de Feu Gabrielle Cerre, Wilmette, Jean Baptiste Beaubien, Pierre Rousseau, and many others well known to the fur traders of that day.

STILL PLACE OF INTEREST.

It appears that he was associated at the time of his death with Mr. Newberry of Detroit, commonly known as the “Admiral of the Lakes," in the ownership of a vessel for the navigation of the Great Lakes. The old Bailly homestead, as it is called, is still a place of interest to the many visitors who go thither to look upon the place of the first white settlement in this part of the state. Some of the old buildings are standing yet, particularly the old chapel, an old log building that was used by Mr. Bailly in the fur trade, the old kitchen and the old house, since remodeled and weather-boarded. The setting still is one of the most attractive in the community, with its old towering white oaks, elms, maples and other trees that sheltered the wigwams of the Pottawattomies in those primitive days.

After the death of Miss Howe, the homestead was sold to, and is now in the possession of, the Sisters of Notre Dame. It is to be hoped that at some date in the future, a suitable marker will be located on the premises.

The contrast between the environment of the homestead in 1822 and the environment of 1922 necessarily must be sharp. Railroads in the

79

early ‘50s of the last century came hard by, over which the iron horse had made countless trips to and from Fort Dearborn, now Chicago. Railroads, steam and electric, traverse the surrounding country. Over the old trail of those early days, upon which there traveled in single file the native tribes of the Pottawattomies and the Ottawas and a few white adventurers, now winds a macadamized road, over which rolls many an automobile. Farms cover the landscape. A short distance away, a part of the old Detroit-Chicago road, along which rattled the buckboard of the mail carriers of long ago, is this year being appropriated for a cement highway extending between Gary and Michigan City, to be known as “Dunes Highway,” which is destined to be one of the greatest thoroughfares for auto travel and traffic in the central west.

FIRST AIR ROUTE.

A little while ago, one day in May, 1919, while living near the site of the old post, we heard a strange and muffled noise; looking we saw a new mail carrier on the old route leading by the old Bailly homestead. He came not mounted on a steed, with a knapsack on his back, nor on the old rattling buckboard whose arrival brought gladness in the days of long ago; neither did he come in a rapidly rolling railway mail car, laden with tons of letters and periodicals; he was above these antiquated modes of transportation — he was in the air; he had adopted the transportation system of the birds. We saluted our new carrier, but his eminence prevented our recognition of any response. He was on his way from Cleveland to Chicago, and he went right on.

Standing now on a clear and cloudless day on the bluffs just above the beach at which Mr. Bailly loaded his peltries for their long journey to far-away Mackinac in boats operated by hand-propelled oars, one may now see, in looking westwardly across the lake, a tall white tower. It rises amidst a city of nearly 3,000,000 souls. When Bailly loaded those boats at his improvised port, there was no tower nor city there; instead there were less than a dozen houses, or shacks, and less than fifty persons, outside of the fort, which stood at the mouth of the Chicago River, which having since grown tired of its old ways, has reformed and reversed its course, and now empties its waters into the Mississippi. Lands that then went begging for $1.25 an acre, now command $600 an acre. The procession of events along this Indiana shore travels in double-quick step. Nothing in today is quite as it was on yesterday. The photograph of today will merely resemble tomorrow. Who, a hundred years ago, could have foreseen such transformation? What further transformation will the historian of 2022 record?

May I be pardoned a moment for a departure from historical events to an indulgence in a little prophecy? For at some time or other, most of

80

us like to say “I told you so.” May the pleasure be mine! May I guess that

some day there will be a succession of cities all the way from Waukegan to

Michigan City, yea, a chain of alternating cities and parks extending

southerly and northerly all of the way from Green Bay to Charlevoix and old

Mackinac? Are my hearers a little skeptical? Then remember the fate of a

certain southern congressman, who some years ago spoke in tones of derision

of the “Zenith City by the unsalted sea.” Unwittingly, he was mocking

Destiny. His own generation lived to see a real zenith city by that unsalted

sea, and the historic irony of the Hon. Proctor Knott of the forty-first

congress now reads like a prophecy. The dream of Mr. Bailly may yet come

true. There may yet be a harbor at the south end of this inland sea, in

which ships will anchor, bearing the flags and the commerce of all the

maritime nations of the world.

NAVIGATION OF

HISTORY OF THE LAKE AND CALUMET REGION OF INDIANA

FOREWARD

AN APPRECIATION

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I - Geology and Topography

CHAPTER II - The Mound Builders

CHAPTER III - Days of Indian Occupancy

CHAPTER IV - Early Explorations

CHAPTER V - Border Warfare

CHAPTER VI - Lake and Calumet Region Becomes Part of United States

CHAPTER VII - After Wayne and Greenville - Tecumseh and the Prophet

CHAPTER VIII - Indian Peace

CHAPTER IX - Early Settlements and Pioneers - County Organization

CHAPTER X - Townships - Towns - Villages

CHAPTER XI - Pioneer Life

CHAPTER XII - The Lake Michigan Marshes

CHAPTER XIII - Agriculture and Livestock

CHAPTER XIV - Military Annals

CHAPTER XV - The Lake and Calumet Region in the World War

CHAPTER XVI - The Newspapers

CHAPTER XVII - The Medical Profession

CHAPTER XVIII - The Bench and Bar in the Lake and Calumet Region

CHAPTER XIX - Churches

CHAPTER XX - Schools

CHAPTER XXI - Libraries

CHAPTER XXII - Social Life

CHAPTER XXIII - The Dunes of Northwestern Indiana

CHAPTER XXIV - Banks and Banking

CHAPTER XXV - Transportation and Waterways

CHAPTER XXVI - Cities

CHAPTER XXVII - Industrial Development

CHAPTER XXVIII - Chambers of Commerce

Transcribed by Steven R. Shook, December 2022