History of Lake, Porter, and LaPorte, 1927County history published by the Historians' Association . . . .

Source Citation:

Cannon, Thomas H., H. H. Loring, and Charles J. Robb. 1927.

History of

the Lake and Calumet Region of Indiana, Embracing the Counties of Lake,

Porter and LaPorte: An Historical Account of Its People and Its Progress

from the Earliest Times to the Present.

Volume I. Indianapolis, Indiana: Historians' Association. 840 p.

HISTORY OF THE LAKE AND CALUMET REGION OF INDIANA

CHAPTER III.

DAYS OF INDIAN OCCUPANCY.

THE AMERICAN INDIAN -- PROBABLE ASIATIC ORIGIN -- ALGONQUINS AND IROQUOIS --

THE INDIANA TRIBES -- THE POTTAWATOMIES -- SHAUBENEE -- JOHN R. CHAUDONIA --

ALEXANDER ROBINSON.

12

The name “Indian” was bestowed by Columbus upon the copper colored natives who greeted him when he first set foot on the soil of the New World and which he at that time supposed constituted a portion of India. The name has remained and with the prefix “American” includes all the native races inhabiting both North and South America. Speculation in regard to the origin of the American Indian has no limit. By some, the tribes are considered an aboriginal and single stock, while still others claim that they are derived from the grafting of old world races on a true American race. Anthropologists for many years have been making a study of thousands of Indian crania and skeletons in an effort to determine their origin and they have found that while there is a number of sub-types and a range of individual and localized differences, yet, fundamentally they appear to belong to one large strain of humanity, the yellow-brown branch, which included the Mongol, the Malay, the Eskimo and a large element of the Chinese, Japanese, Tibetans and Polynesians.

Dr. Ales Hrdlicka, famous anthropologist of the United States National Museum, who has given years of study to this subject, believes the ancestors of the American Indian came from Northeastern Asia and found a startling resemblance in the inhabitants of Tibet to the American Indian. He has formulated the theory that the ancestor of the Indian came to America thousands of years ago by way of Siberia and across Bering Strait and thence down the West Coast as far South as even Peru where the remains of very ancient peoples have been found. Many other anthropologists incline to the theory of Asiatic immigration by means of Bering Strait and when it is considered that these migrations came in dribbles over a long period of time and the different geographical locations and climatic conditions in which the various tribes lived in America, it would be easy to account for any differences in their characteristics. Doctor Hrdlicka’s theory seems sound. The caves of the old world yield evidence of very ancient man, his bones, his implements, his art, but nowhere in the New World have there been found any caves with evidence to indicate man’s existence on this continent at a very ancient period, and it is a

13

reasonable assumption that man arrived in this country from the other continents.

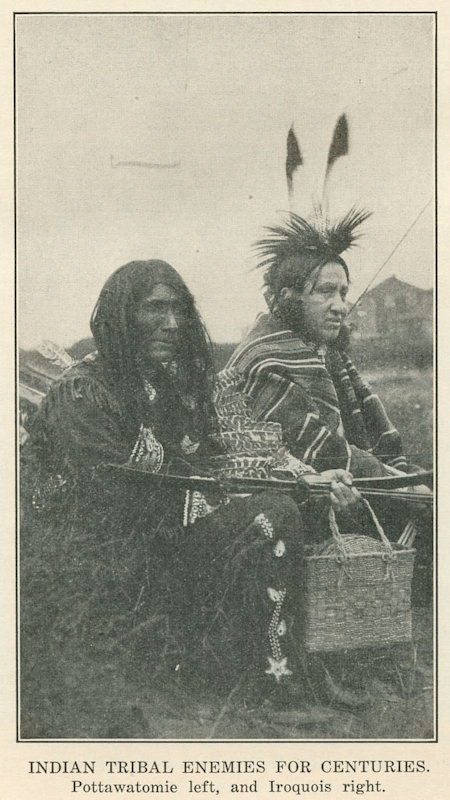

Common physical characteristics of the Indian are the long, lank, figure, jet black hair, brown or copper colored complexion, varying to nearly white, heavy brows with dull sleepy eyes which seldom express emotion, full and compressed lips and dilating nose. The head is square or rounded with vertical occiput and high cheek bones. The Indians in the eastern half of the United States, north of the Carolinas, with whom the whites first came in contact belonged to two great groups — the Algonquin-Lenape and the Iroquois. The Lenni-Lenape section of the Algonquin comprised the five nations of the Delawares, including the Mohicans. The Iroquois included the Senecas, Cayuga, Onondagas, Oneidas, Mohawks, Tuscaroras and Hurons, with a few scattered kindred tribes.

THE INDIANA TRIBES.

The Indians whom the first white explorers met in Indiana or who wandered in its forests were of Algonquin stock although the Mingoes who were a branch of the Iroquois had homes in Ohio and there is little doubt but they frequented Indiana territory. The Indian was an enigma to the white explorers on account of his inconsistencies, and constant intercourse made him a greater puzzle. He was full of contradiction. While enduring cold and hunger without a murmur, facing torture at the stake without flinching and singing his death song while undergoing the greatest physical agony, yet he was capable of great emotion and under some great calamity would mourn and sob wildly in his distress.

Parkman says of the Indian, “He deems himself the center of greatness and renown and his pride was proof against the fiercest torments of fire and steel, and yet the same man would beg for a dram of whiskey or pick up a crust of bread thrown to him like a dog from the tent door of the traveler. At one moment — wary and cautious to the verge of cowardice, in the next — abandon himself to a very insanity of recklessness. Ambition, revenge, envy, jealousy, were his ruling passions and utter intolerance of control lies at the basis of his character. With him, the love of glory kindles into a burning passion and to allay its cravings, he will dare cold and famine, fire, tempest, torture and death itself. Among his characteristic traits are a sleepless distrust and rankling jealousy. He is trained to conceal passion, not to subdue it. He has been aptly imaged by the hackneyed figures of a volcano covered with snow and no man can say when or where the wild fire will burst forth.”

His senses were keen, but his reasoning was rudimentary and his thoughts were primarily on war and on the chase. Wrangling and quarrels were strangers to an Indian dwelling and he had his affections concealed

14

under a mask of chilling reserve. A great weakness was his failure to provide ample food and supplies for the long winters and that he survived many winters is a tribute to his wonderful physical strength and endurance qualities and ability to withstand privations. It would seem as though experiencing hunger as he often did during the winter time that he would make ample provision for storing food supplies for winters in succeeding years, but observations of the early explorers show this was not the case.

He had his own laws and customs, communicated with others in writing by means of rude hieroglyphics and lived in villages. The Indians were all fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters and every child was a son or daughter of the whole tribe and the line of descent was reckoned in nearly all the tribes through the mother instead of through the father. He hunted, fished, trapped, and fought the battles of his tribe but took little interest in trade until he found that furs could be exchanged at the trading post for articles needed. Hunting and trapping fur bearing animals which before was only necessary for his personal warmth and comfort and that of his family, then became a regular occupation. They made their own clothes, canoes, paddles, weapons of war and chase and were noted for their basket weaving. While their name became almost a synonym for treachery, yet acts of kindness were rarely forgotten and the decisions of their tribal council in matters of right and wrong among themselves showed a true conception of justice.

THE POTTAWATTOMIES.

How long the Pottawattomies were in possession of the Lake and Calumet region of Indiana is not known. The many trails which crossed the Lake region of Indiana showed it was frequently visited by tribes of Indians from other regions, but the Pottawattomies made it their home. Their lives were similar to that of most of the Indians and like the Algonquin tribes generally they did not have the extreme savage nature of the Iroquois. Their usual camping places were along the shores of the Lakes and Calumet River and on the islands of the Kankakee. Their village wigwams were substantially constructed and their birch bark canoes were well made and many of them of large size. The squaws cultivated gardens for their staple product corn, but grapes were grown in some territory and they were experts in reducing maple sap to sugar. Their winters were spent in successful trapping as they were in the heart of the most wonderful fur bearing territory and they used many ponies in hauling their furs.

Some large burial grounds throughout the Lake and Calumet region indicate where long time villages were established and with the burial

15

ground was the dancing ground. The Pottawattomies were kindred with the Ojibwas and the Ottawas and were united with them in a rather loose confederacy. They were closely allied in blood, language, manners and character. The Indian generally was noted for his absence of reflection, making him grossly improvident and unfitting him for pursuing any complicated scheme of war or policy, and it is this absence of reflection which made him suffer from want during the winter in failing to make proper provision in maintaining himself during the long cold season. In this respect the Pottawattomies were distinct from their associated tribes

16

and did not neglect agriculture and though wandering many months of the year among the prairies and forests they tilled the soil sufficiently to make reasonable winter provision for their wants.

The Indians generally were very susceptible to the power of oratory and the Pottawattomies were easily victims to its sway and when oratory was supported with presents, the Pottawattomies quickly were pursuaded to take part in struggles in which they had no special interest. They were always engaged in border warfare and notwithstanding they suffered grievously on many occasions, they could always be induced to make a new alliance. Hence we find them on the side of the French in fighting the English and on the side of the English in fighting the Americans and always a party to every Indian coalition against the whites excepting in the Black Hawk war in which only a few young warriors joined Black Hawk. They were one of a dozen tribes whose activities were responsible for constant border warfare with the loss of the lives of thousands of settlers.

Although the Indian generally was noted for dissimulation, it can be said of the Pottawattomie that he was a past master of this Indian characteristic, and his duplicity was so pronounced and so continuous that with a few notable exceptions among the tribes, he never had the confidence of the early representatives of the various white governments. His promises were worthless and his good faith ever questioned, and the chiefs generally seemed to over-exert themselves to demonstrate their absence of integrity. A pronounced example was Winnemac, who in many ways convinced Harrison of his great friendship, and even had a loaded pistol in pretended readiness to kill Tecumseh at the first meeting with Harrison at Vincennes when it seemed as though Tecumseh would attack Harrison.

Yet later events disclosed he was actually in alliance with Tecumseh but so long as he could serve Tecumseh’s interests best by asserting his great friendship for the Americans, he would do so, and though always receiving generous treatment in supplies, he over night became their open enemy and joined Procter’s Indians. He was killed by an Indian Scout. Bright Horn, who was a real friend of the Americans. There were so many of the Winnemac type of Indian at this period that Americans became doubtful of all Indians and Pottawattomies particularly, and many real Indian friends of the Americans, like Logan, were unjustly under suspicion as a consequence. A study of the Pottawattomies show that the most pernicious elements in Indian character were generally prominent and an absence of the higher virtues which distinguish the Wyandots, Delawares, and some other tribes.

17

CHIEFS OF THE LAKE REGION OF INDIANA LOYAL TO AMERICAN.

In striking contrast to Winnemac and other chiefs of the Pottawattomie tribe, is the story of Shaubenee, of Shaubena, as most of the older historians give his name. While Shaubenee was not a Pottawattomie he was kindred to them and was born in Canada in 1775. He was a grand-nephew of Pontiac and on a visit with a hunting party to the Pottawattomie country, he married a daughter of their principal chief whose village was on the shore of Lake Michigan within the present territory of Chicago. When forty years of age he was a war chief of both the Ottawa tribe with whom he was directly connected and also the Pottawattomies and joined Tecumseh in his tribal federation.

Shaubenee was next in command to Tecumseh at the battle of the Thames and when Tecumseh fell, Shaubenee ordered a retreat of the Indian forces. He recognized the futility of continuing against the whites and ever afterwards refused to wage war against them, for which reason he was deposed as war chief but continued to be the principal peace chief. He was the head of the Ottawas, Pottawattomies and Chippewas, for about twenty years, and maintained his friendship for the whites. For his loyalty there was reserved for him two sections of land near Pawpaw Grove, Illinois, when the Indians ceded their Illinois lands to the United States, but he soon lost title to this land. In 1859 twenty acres of land were bought for him by some of his white friends and they also built a house for his occupancy, where he died in 1859.

JOHN B. CHAUDONIA mixed parentage, was another striking figure of this period, whose loyalty to the Americans earned the good opinion of the Government and the respect and friendship of the settlers. His mother was a Pottawattomie and a sister of Topinebee, a leading chief of the tribe, and his father was a Frenchman. Chaudonia showed his friendship during the massacre at Chicago by saving the lives of the Kinzies and also Captain Heald and his wife and made strenuous efforts to save all the Americans who surrendered. He was a valuable scout for the Americans and was once taken prisoner by the British but escaped. He was with Harrison’s army at the battle of the Thames and after his military service was over, engaged in fur trading.

Chaudonia was an important influence in neutralizing the efforts of Black Hawk, who sought the assistance of the Pottawattomies in the so-called Black Hawk war, and, with some other chiefs, prevailed on the Pottawattomies to maintain the peace agreement of 1816, and convinced them of the futility of again fighting the Americans. The Government provided liberally for him in land grants to take care of his future, but he was very improvident and in spite of the assistance rendered him, was occasionally in want. He died at South Bend in 1837. Ten years after

18

his death the Government gave his widow, who was a French woman, and his two children an additional section of land and she lived with her grandchildren until her death in 1876 at St. Joe. Two of her grandchildren, Charles T. Chaudonia and Edward Bresett, were Union soldiers during the Civil war and made excellent records.

The last of the principal chiefs of the Pottawattomies was ALEXANDER ROBINSON whose Indian name was Chee-Chee-Bing-Way “Blinking Eyes,” who died near Chicago in 1872 and was said to be more than 100 years old. He was of mixed blood, Indian, French and English, and was a contemporary of Joseph Bailly and about 1810 was engaged in the fur and supply trade on the southern shore of Lake Michigan in the employ of John Jacob Astor of New York. It was said that among other commodities he handled corn which was brought to Chicago for distribution to other Lake markets. He was on his way to Fort Dearborn, Chicago, in August, 1812, when he was warned of the impending massacre at the Fort.

Hiding his canoe at the mouth of the Big Calumet, he continued on foot to Chicago. He did all he could personally to save the survivors of the massacre which took place just before his arrival and aided in bringing some of them to white settlements. In 1825 he became the principal chief of the Pottawattomies. As the head of the Pottawattomie tribe he called the Indian council together in Chicago in 1832 for the purpose of main¬taining peace during the Black Hawk war and again in 1836 he presided over the gathering of 5,000 Pottawattomies assembled in Chicago for departure on their journey to the reservation in Kansas.

NAVIGATION OF

HISTORY OF THE LAKE AND CALUMET REGION OF INDIANA

FOREWARD

AN APPRECIATION

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I - Geology and Topography

CHAPTER II - The Mound Builders

CHAPTER III - Days of Indian Occupancy

CHAPTER IV - Early Explorations

CHAPTER V - Border Warfare

CHAPTER VI - Lake and Calumet Region Becomes Part of United States

CHAPTER VII - After Wayne and Greenville - Tecumseh and the Prophet

CHAPTER VIII - Indian Peace

CHAPTER IX - Early Settlements and Pioneers - County Organization

CHAPTER X - Townships - Towns - Villages

CHAPTER XI - Pioneer Life

CHAPTER XII - The Lake Michigan Marshes

CHAPTER XIII - Agriculture and Livestock

CHAPTER XIV - Military Annals

CHAPTER XV - The Lake and Calumet Region in the World War

CHAPTER XVI - The Newspapers

CHAPTER XVII - The Medical Profession

CHAPTER XVIII - The Bench and Bar in the Lake and Calumet Region

CHAPTER XIX - Churches

CHAPTER XX - Schools

CHAPTER XXI - Libraries

CHAPTER XXII - Social Life

CHAPTER XXIII - The Dunes of Northwestern Indiana

CHAPTER XXIV - Banks and Banking

CHAPTER XXV - Transportation and Waterways

CHAPTER XXVI - Cities

CHAPTER XXVII - Industrial Development

CHAPTER XXVIII - Chambers of Commerce

Transcribed by Steven R. Shook, December 2022